A History of Equine Anatomy – A Journey Through Time

- Gillian Higgins

- Jun 30, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 14, 2025

At Horses Inside Out, our mission has always been clear - to show how a deeper understanding of anatomy can enhance performance and reduce the risk of injury. We all want what’s best for our horses. That’s why we keep learning, striving, and seeking new ways to improve their welfare.

However, we’re not the first to explore the relationship between anatomy and movement. In fact, the study of equine anatomy has a rich and fascinating history. I’ve always found it inspiring to look back and learn from the pioneers who paved the way. So, in this article I’m going to take you on a short journey through the past - one filled with curiosity, courage, and quite a bit of gruesome work!

The Artist-Anatomist, George Stubbs

Let’s start in the mid-18th century with George Stubbs, a man whose work changed how people saw horses, quite literally.

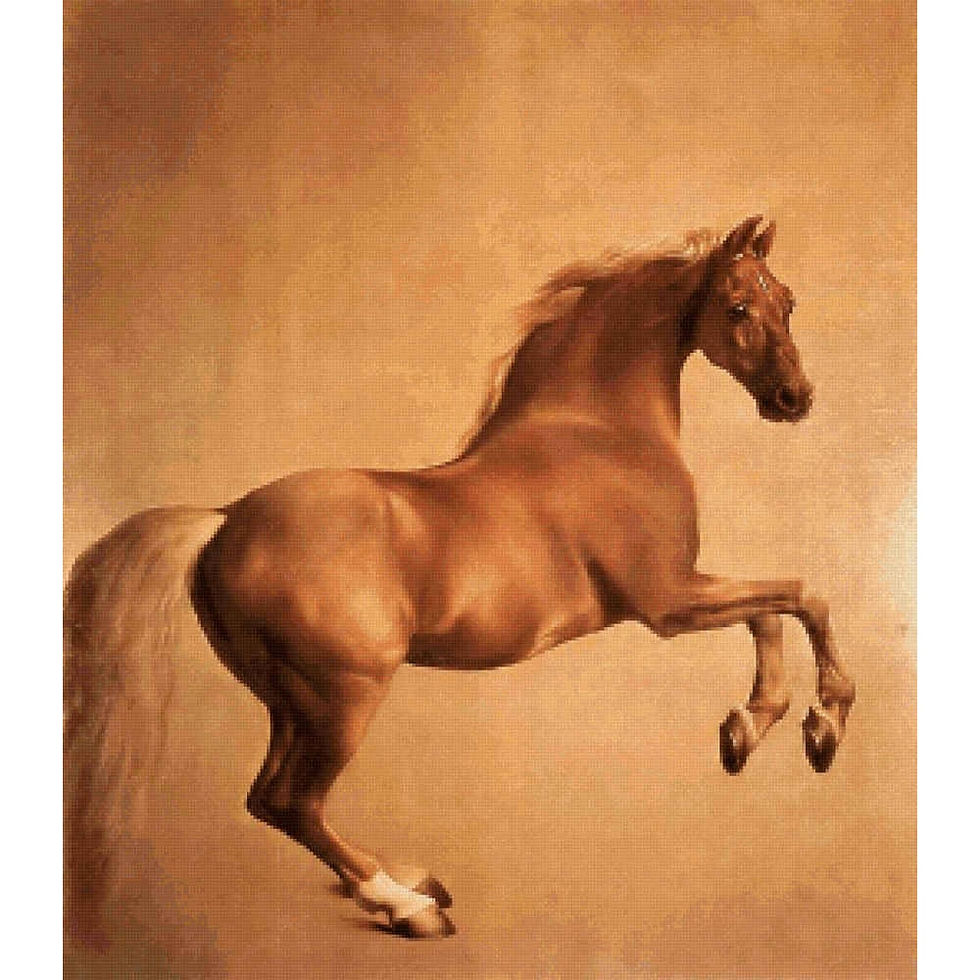

You might know him best for his famous painting of the Marquess of Rockingham’s racehorse Whistlejacket, but it wasn’t just his talent as an artist that set him apart from others. It was his extraordinary understanding of equine anatomy.

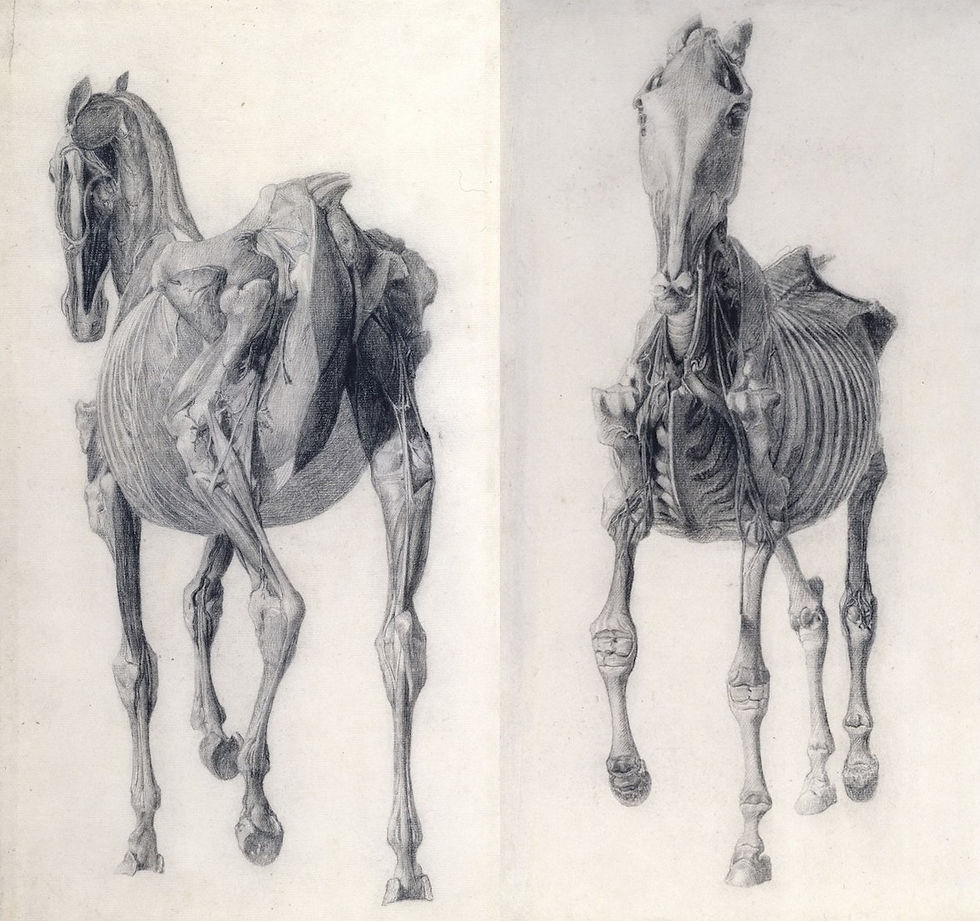

Between 1756 and 1758, Stubbs secluded himself in a farmhouse in Horkstow, near Hull. For 18 months, he dissected horses in painstaking detail, layer by layer, spending a whole day measuring, drawing and describing what he found.

The conditions were far from pleasant. He claimed to have worked on one single carcass for 11 weeks. The smell must have been unbearable.

What came from this dedicated study was The Anatomy of the Horse, published in 1766. It was a game-changer. Before Stubbs, the only major anatomical reference was Carlo Ruini’s book from 1598 and much of that was based on human anatomy, full of inaccuracies that had been copied for generations and used by farriers and vets of the day. Stubbs offered something new and the truth as seen through careful dissection and observation.

His work didn’t just benefit artists. It laid the foundation for a more accurate understanding of horse anatomy and was instrumental in improving equine welfare and furthering veterinary knowledge of the time.

The Great Debate - How Do Horses Really Move?

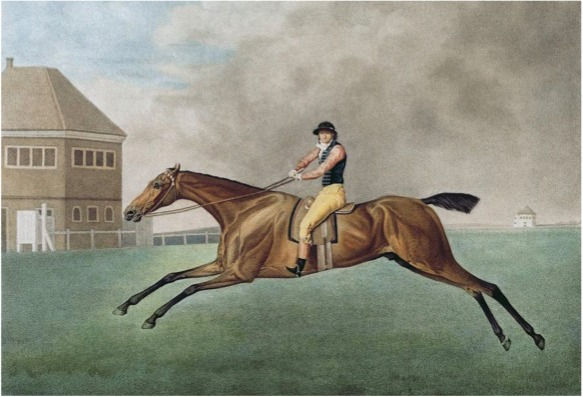

Despite Stubbs’ incredible insight into structure, there was still a lot of confusion about how horses actually moved - particularly at faster gaits. Artists often painted galloping horses that showed a moment of suspension with the fore and hind limbs stretched out in front and behind, something that wasn’t quite accurate.

This wasn’t a new debate. Way back in Ancient Egypt and Greece, people were already questioning how horses moved. Plato even mentioned it. Xenophon, a renowned horseman of the time, stressed the importance of understanding limb function, sadly none of them left detailed descriptions or evidence of how movement was executed.

A step forward came in 1659 with A General System of Horsemanship by the Duke of Newcastle. It included a chapter on the horse’s natural paces. However, even his descriptions of faster gaits were still not quite right. It wasn’t until the late 1800s that the truth about equine movement became clear.

Edward Muybridge, the Genius Who Captured Motion

In 1872, in San Francisco, things were about to change. Leland Stanford, a wealthy American businessman, breeder and owner of Standardbred and Thoroughbred racehorses wanted to prove how horses move. Was there really a moment of suspension in the gallop? To find out, he hired Edward Muybridge, an English-born photographer.

At that time, photography was in its infancy. Exposure times were long. Subjects had to stay still - neck braces were often used, and this is why no one smiles in early portraits, anything that moved came out as a blur. Muybridge initially thought capturing a galloping horse seemed impossible.

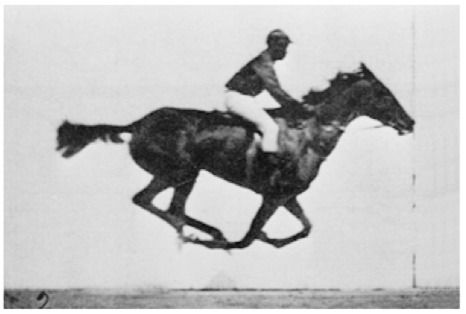

Through months of experimentation with various equipment and chemicals, he significantly reduced exposure time and in the end succeeded. He captured a single image of one of Stanford’s racehorses mid-gallop.

Muybridge didn’t stop there, Stanford then wanted to capture a sequence of photographs showing the horse’s full gallop.

Using 12 specially designed cameras, which Muybridge designed himself, lined-up parallel to the horse’s path and were triggered by his feet, he created a full series of 12 photographs showing the complete stride cycle.

Taking 11 of these images and using his own invention, the zoopraxiscope, Muybridge was able to show a slow-motion version of the galloping horse.

Although Stanford later downplayed Muybridge’s contribution in his book The Horse in Motion, crediting him only in a technical appendix, Muybridge’s genius couldn’t be denied. He moved on to the University of Pennsylvania, here he developed, improved and refined his system and method for recording the action of the horse. This photograph shows his setup of 24 cameras and you can see the trip wires in the foreground used to set off the cameras. He also had other lines of cameras to capture the same movement from in front, behind and oblique angles. This resulted in the most comprehensive study of animals in motion that the world has ever seen - between 1883 and 1886 he made a total of 100,000 images working under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania. These included horses in every gait and performing a wide range of movements.

His final works remain essential references for students of animal locomotion to this day. However, in the 130 odd years since these photographs were taken, preferred breed types and riding styles have changed in many of the photographs and particularly in this one. We can see the horse's movement is influenced by the rider. This is not the only horse to be photographed with its mouth open and the way of going clearly influenced by rider and tack - a reflection, perhaps, of what was normally accepted at the time.

From Past to Present

What fascinates me most and leads to the question about what is normal versus what is correct and this is something that still applies today. It’s amazing to think how the ingenuity and tenacity of George Stubbs and Edward Muybridge has paved the way for anatomists, biomechanists, veterinarians, researchers and equestrians of today.

It’s this that is a big part of what inspires my own work and led to me embark on a project that was to last five years. Where I created a modern catalogue of equine movement. One that shows horses in all gaits and a variety of movements all shown through the unique lens of Horses Inside Out. The end result was a book and accompanying online video course, Anatomy in Action.

It’s the ingenuity of people like Stubbs and Muybridge that still continues to guide us. Their determination opened doors and their legacy lives on and is reflected in every horse we care for.

I hope you have enjoyed this look at the history of equine movement and anatomy and if you are keen to learn more our Equine Anatomy Exhibition is something you won't want to miss. Inside the Horse - Anatomy for Better Riding, Training, and Care runs from the 11th - 23rd August 2025 at HIO HQ, Wavendon Grange, Old Dalby Leicestershire. This unique exhibition offers a fascinating journey beneath the surface of the horse, blending science, art, and practical equestrian knowledge. Come and spend a few hours to deepen your understanding and appreciation of the horse.

Comments